Lawmakers are getting more involved in school decisions.

The Nebraska Legislature signed the Financial Literacy Act, LB 452, in August 2021, adding Personal Finance as a requirement starting with the 2023-24 school year. Following that, the Computer Science and Technology Education Act in 2022, LB1112, made Computer Literacy a requirement starting with the graduating class of 2028.

Papillion-La Vista South principal Mr. Jeff Spilker expressed concern about the new requirements reducing the number of choices students would have for their class schedules.

“When we add two new required electives, I worry that’s hurting flexibility of a student’s schedule to pursue some of their own personal passions that may lie outside of core requirements and now elective requirements,” Spilker said. “I worry about if a kid wants to do band and a world language on top of core classes, what is left out there for them to pursue?”

Spilker said students’ involvement and opportunities might suffer: “[They] already have an incredibly busy schedule, especially because our activities are very important to our students.”

Sen. Jana Hughes, as vice chair of the Nebraska Legislature’s Education Committee, takes an active role in the creation, discussion and passing of legislation implemented in Nebraska’s public schools.

She said that process saw a big change amid the pandemic in 2020.

“COVID started a lot of things,” Hughes said. “Many schools, state by state, handled COVID very differently. Nebraska handled COVID, in my opinion, the best anybody could.”

The state managed to have most students back in the classroom for the start of the 2020-21 school year.

“Places like Chicago or California kept kids physically out of school for over a year,” Hughes said, “and because of that, you see a rise of kids who cannot read, have poor test scores, and are lacking developmentally.”

The success of Nebraska’s pandemic response led state legislators to assume a bigger role in influencing school policy going forward.

“Nebraska senators make the assumption that they have to continuously get into schools and change the laws due to the success we saw post-COVID,” Hughes said. “They are constantly combating issues by pushing legislation to help our kids.”

That has had an impact on school funding, particularly in the area of special education.

Hughes said, because of LB583, 80% of special ed costs are now covered.

“If you had a kid who was in a wheelchair, required a feeding tube, and needed a one-on-one paraprofessional, and your cost to send them to school was $100,000 a year, now instead of local taxpayers paying the majority of that, the tab is picked up 80% by the state,” Hughes said. “Prior to our state doing this, only about 40% of the cost was covered.”

Senators aren’t the only ones who can advocate for this legislation. School administrations such as Nebraska Association of School Board Members also advocate for change.

“If school board members are seeing a certain trend or they think the legislation needs to change, they will vote on it and seek a senator who will start a bill for them,” Hughes said.

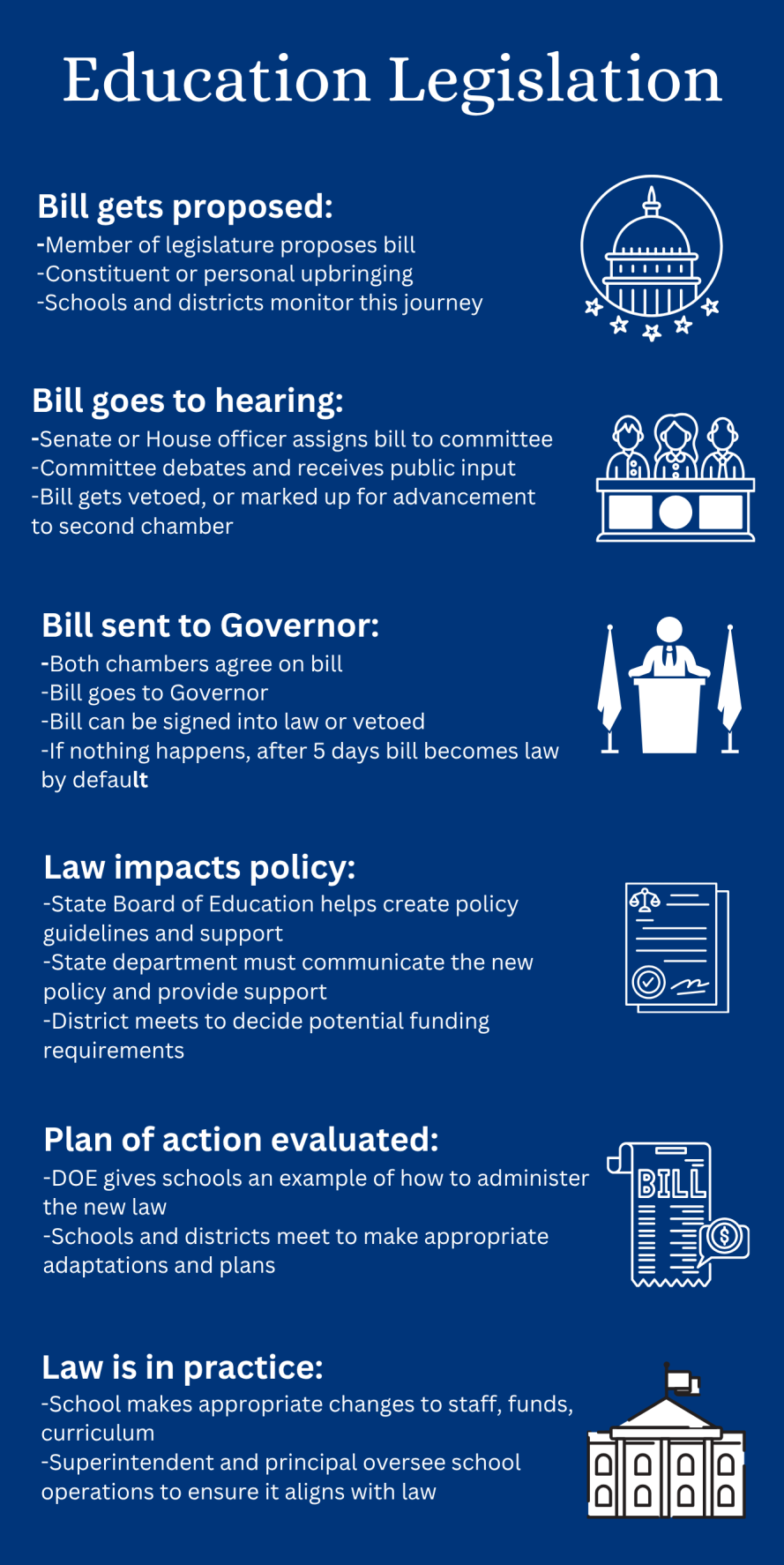

When a piece of education legislation is passed, the Nebraska Department of Education will create a “model policy” that could potentially go into school districts’ handbooks. Once a policy is officially set, it is up to a school board to decide how they want to enforce it.

At a district level, PLC Schools superintendent Dr. Andrew Rikli believes parent engagement regarding education has has an impact on new legislation.

“Multiple factors appear to contribute to increased legislative attention to education, including nationwide discussions about student safety, academic outcomes, technology use in schools, and property tax issues,” said Rikli.

Topics such as student technology use, parent notification procedures, and library material access have been managed through local school boards. Recently, the state legislation has trumped that.

Rikli said balancing community needs with state mandates has been one extra challenge.

“Implementation requires districts to update policies, communicate changes to families, and ensure staff understand new requirements,” Rikli said. “Districts are working to balance compliance with existing local priorities and resource allocation” Rikli said.

Navigating the rapidly changing state legislature is something Papillion-La Vista South’s principal Jeff Spilker is no stranger to.

Spilker has made it a priority to observe the changing status of these educational bills to be best prepared for the possible changes they could bring.

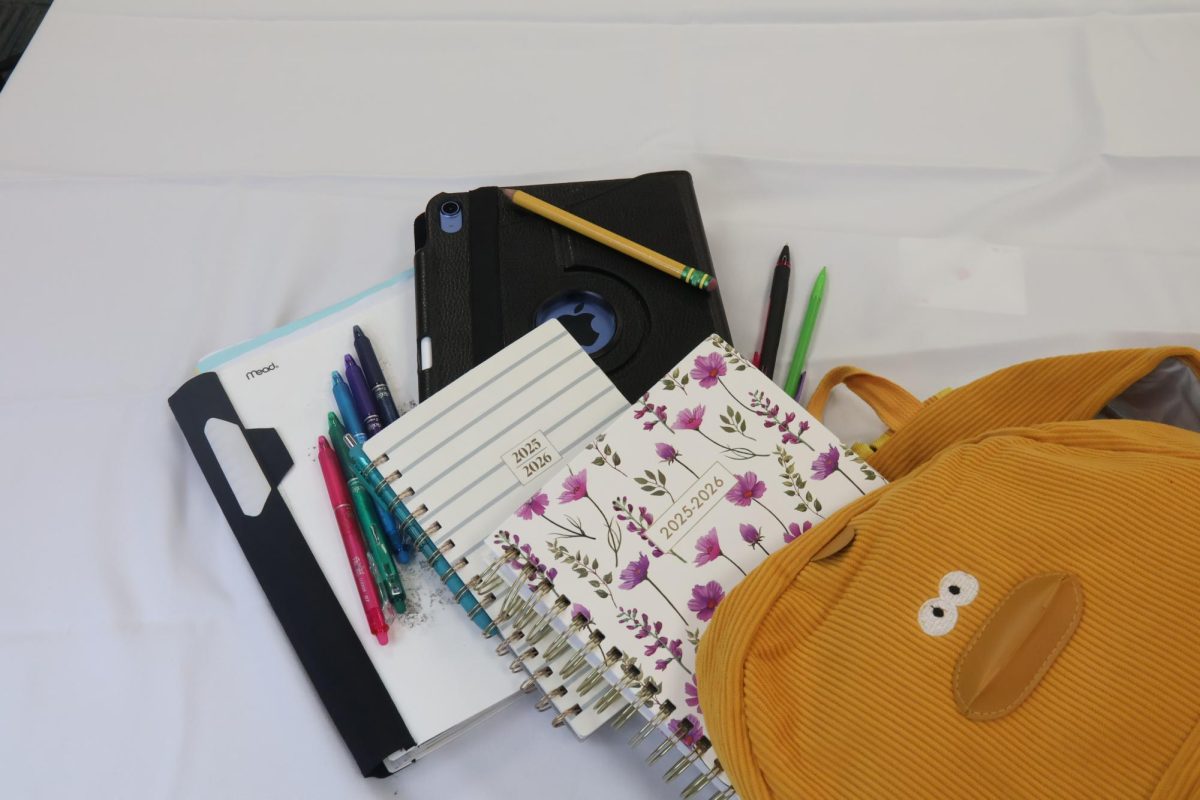

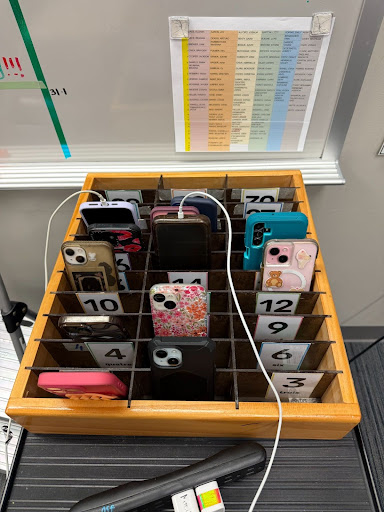

One piece of legislation Papio South was already coming to head on was the 2025 cell phone ban.

Adopting ‘bell to bell no cell,’ Papio South had already been progressing toward cell phone restrictions, so for Spilker, it was just one extra step.

The previous expectation was cell phones were to be put away during lecture time, and ultimately were up for teachers to decide their classroom rules.

The addition of LB140 requires every district to set restrictions of cell phone usage on school grounds.

“Students see the cell phone regulations most frequently during the school day,” Spilker said.

“Since the state legislature has been involved in education, it’s something we have to consistently monitor. We want to make sure that our voice is heard, because those new bills definitely impact the way we run the school, the learning, and our students,” Spilker said.

“We always have to be aware of the changes, and be ready to adapt to make changes when bills do pass,”

These changes include potentials of hiring more staff, needing more or new materials such as a phone caddy, or navigating how to administer new mandates.

Spilker evaluates the status of these potential bills alongside an administrative supervisor group who tracks the progress of them.

![Pictured above is a structure that displays the names of Nebraska Vietnam veterans in order to “honor [their] courage, sacrifice and devotion to duty and country.”](https://plsouthsidescroll.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Trey_092625_0014-e1760030641144-1200x490.jpg)