Inspired by another teacher’s progressivism project, Social Studies teacher JD Davis gave his freshman students the freedom to campaign for school changes in order to broaden the view of their new school environment. “With younger students, you want to believe that they start looking at things differently. They’re four years away from adulthood, and a lot of the things that go on are starting to affect them, even if they don’t realize it,” Davis said. “I think it’s one of those things that help kids find their voice.”

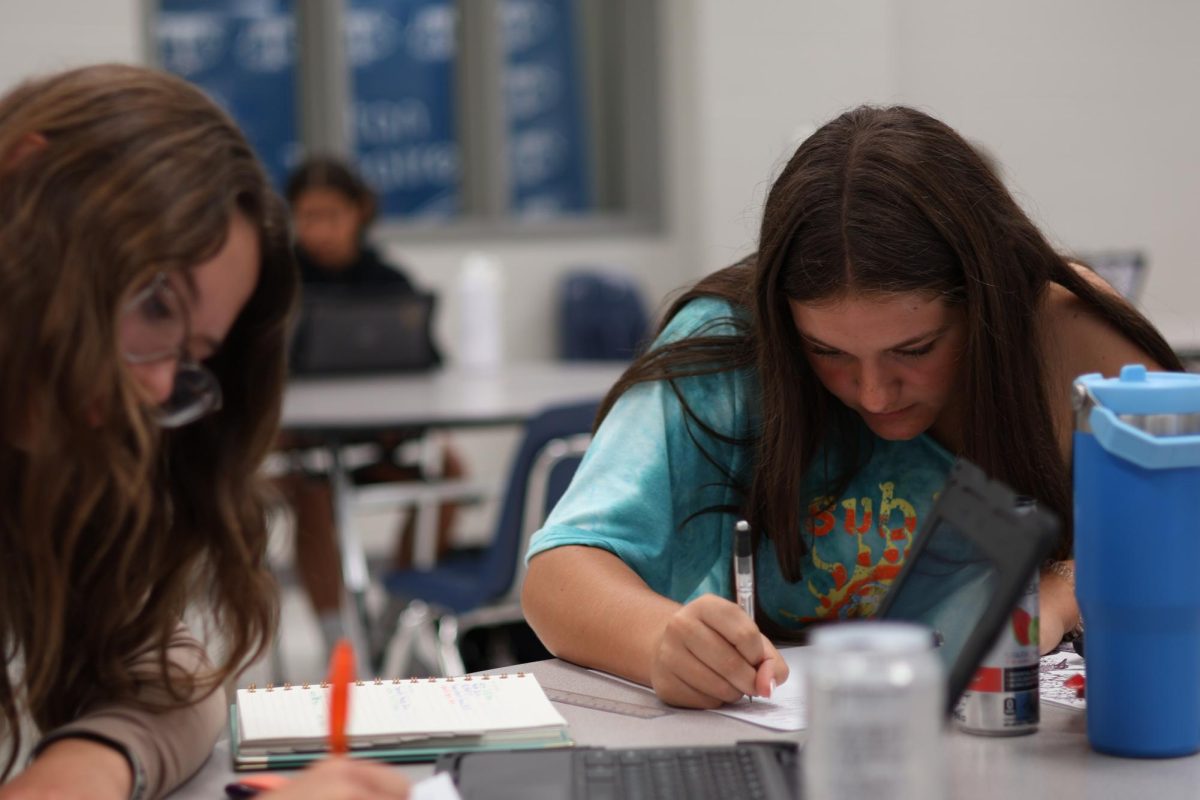

Davis wanted to allow these students to start the conversation about school wide issues. The project was a way to allow even the kids who tend to be more quiet to express their ideas or grievances.

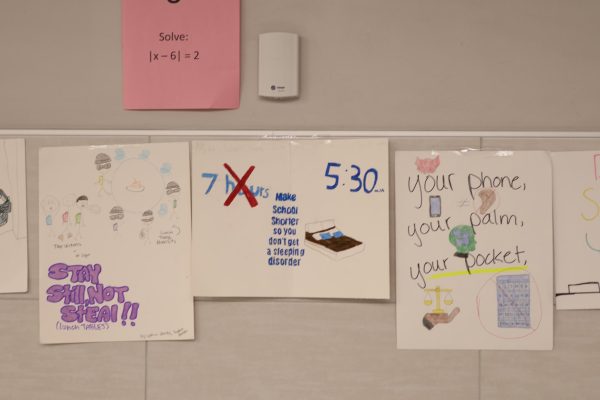

As the students utilized the chance to express their ideas, either individually or in pairs, they created a small poster in order to display their desired change. Though there was a diverse array of reforms that the freshman wanted to enforce, Davis said that, every year, there were always notable topics that students felt the need to advocate about. This year, students had felt the need to speak about the newly implemented phone policies. Although many still branched off to address different issues, the idea of changing the policies was considered by freshman on account of the new rules.

Freshman Katelyn Parks and her partner focused on class credits. Parks’s poster was decorated with different symbols, each one depicting a sport, club, or other extracurricular that students have the chance to participate in. The poster was advocating for those kinds of extracurriculars to be worth credits, which are earned as a result of passed classes and allow students to graduate come the month of May.

Parks believed that earning credits for extracurricular activities could give students a head start on graduation requirements and add an incentive to participate. Clubs and sports are a significant part of the high school experience, with most students participating in at least one. Parks went on to say that it was simply convenient for those activities to have those extra credits.

“When you look at yourself and you say…, ‘I need more credits, I need more opportunities.’ Why don’t we just have [that] sport be a credit?” she said.

Freshmen Rylee Harter and Alayna Kennon had a different idea. On their poster, they broke down why freshmen should have the opportunity to join academies – which, in the present time, are only available to upperclassmen. There are different academies, such as Zoo Academy, or Education Academy, and Harter said those kinds of opportunities could be useful for freshmen who already know what they want to do in the future.

“I think that it would be a good idea to include more academies…” she said, “Because a lot of us have decided what we want to do with our future, and I feel like … it can help us to achieve that goal.”

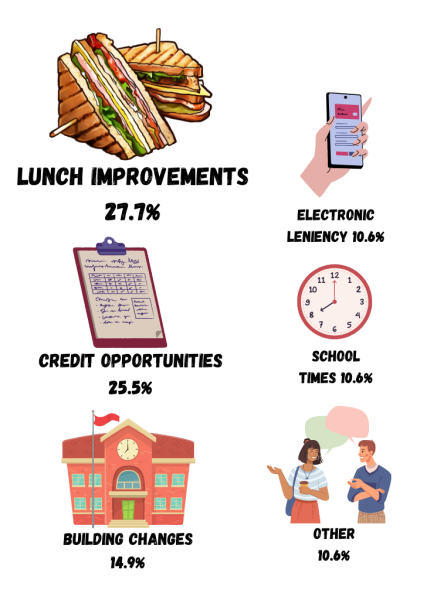

In saying that, however, it should be noted these stories are far from the only thing that freshmen felt the need to speak on. Pooling together the different posters from 47 participants, their similar ideas were narrowed down into broader categories to get a better idea of some of the trends overall.

All of this to say, the process of an actual policy change is somewhat complicated as a whole. Assistant Principal Mr. Brent Gehring talked about this topic, saying that the size of the change determines how much the decision is handled by PLSHS itself. He explained that small things, such as practices, would be much easier to manage in terms of policy changes. However, changing classes, or adding credits as incentive, would be handled at the district level.

An example of change at the discretion of the high school, Gehring said, would be the cell phone policy. The policy itself was adopted by the building, and isn’t a policy enforced by the district. PLSHS took on the phone policy individually, after advice given from other districts that implemented the changes.

However, that is not to say all practices such as the cell phone policy are made by school – some are decided by the district, such as the school’s policy for cheating. It’s difficult to perfectly distinguish what might be a choice from the school, and what might be chosen by the district. It varies from change to change, and the size of that change, but there tends to be a certain path each of those changes go through in order to be considered.

Gehring broke it down, saying, “It starts [at the school] – and we’ll tell you if we have the power to do that or not… We have a student services department that would probably be the next contact – that would be at Central Office… Then they would work with our cabinet, which is our upper-level management in the district.”

Even then, he explained, the issue itself can still vary enough to fall into the hands of the school board.

Perhaps the highest influence on these kinds of school policy, though, is the state legislature. According to Mr. Jeff Spilker, the Head Principal of PLSHS, the leadership in the Central Office consistently monitors what bills the state is discussing, and what bills they have a chance of passing.

The changes that the state makes are district wide, and things that might have been at the decision of the school can easily be changed that way. The most recent of these changes is a new graduation requirement, being that all Nebraska students must take Personal Finance before graduation.

“Our students that are current sophomores, that are current freshmen, and then classes to come, they all have to have Personal Finance in order to graduate. We did not require that before that bill was passed,” Spilker said.

There was a similar situation the following year, where the state passed another bill that required students to take a Computer Science class in order to graduate. These policies were enforced by the state legislature, as the school itself didn’t have those requirements before.

They can do more than just policy change however, Spilker explained. The different bills can impact student behavior requirements or activities; anything that the state passes can impact the school heavily, it only depends on the purpose of the bill.

Policy change is a long, complex process involving many levels. Decisions are not always easy for the school, and, at times, are out of the school’s hands. Yet, it all starts here at the high school level.

![Pictured above is a structure that displays the names of Nebraska Vietnam veterans in order to “honor [their] courage, sacrifice and devotion to duty and country.”](https://plsouthsidescroll.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Trey_092625_0014-e1760030641144-1200x490.jpg)