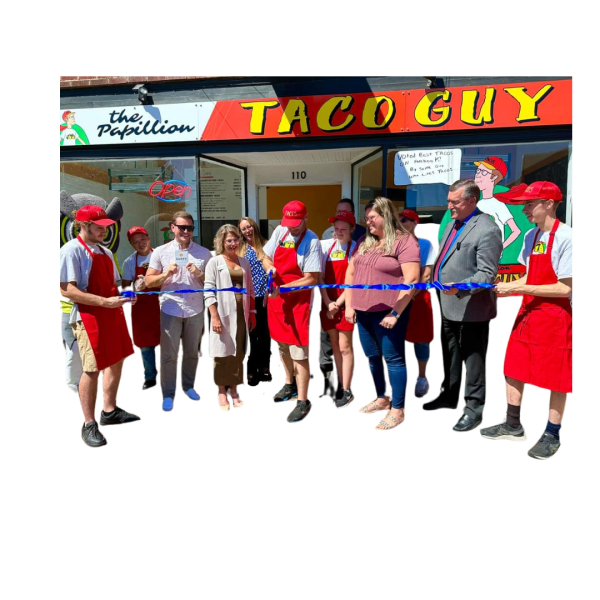

Since the opening of The Papillion Taco Guy, Scott Nedved, owner of the business, has balanced giving back to the community while also operating a cart, food truck, and restaurant.

With a restaurant, located at 110 N Washington St., Nedved is able to donate a portion of profits to local charities.

“I think it would be neat if we could be a good influence, do something positive,” Nedved said. “I think it would be cool if all companies did that.”

Most recently, March profits went toward CEDARS, a nonprofit that helps children in the foster system.

This allowed customers to enjoy both tacos and giving back.

“We can give some money to them and we can highlight them, and do a cool thing with that,” Nedved said.

Of all the different organizations to choose from, Nedved prefers the ones with a more local impact. “I really wanted to focus the money in here,” he said.

While Nedved is fairly new to Papillion, he’s not far from home.

“I grew up in Millard actually, after college, I moved back,” Nedved said. “Moving to Papillion was really driven by my wife, who loved the area, and I had always also liked it so we looked for homes here when timing was right.”

Nedved, who graduated from Iowa State in 2005 with degrees in Management and Marketing, had been working in food service since he was 15.

Nedved’s first trailer, known as Braai Time, opened in April 2018. In January 2020, Braai Time had the opportunity to park outside a construction project where food trucks were required five days a week: breakfast, lunch and dinner. It was there that tacos became his specialty.

“Oddly enough, when we would go into where the construction workers were, they decided tacos. It could’ve been anything,” Nedved explained. “We could’ve been the sandwich guy, the philly guy, or the gyro guy.”

Within a couple of months, the COVID pandemic shut down that operation.

“We could no longer be outside because people congregated around food trucks, and they didn’t want that,” Nedved recalled.

With social distancing as a new obstacle, the business had to adapt.

“We had just enough money to buy a cart. I said, ‘We’re going to do something different, under the same name, but it’ll just be on the corner. We can’t do our full menu but we’ll just do tacos, just to keep retail going until this whole thing blows over,’” Nedved said.

In a time of uncertainty, Nedved kept a positive outlook.

“It was fun,” he said. “I love working cart. It’s all customer interaction, which I really enjoy.”

Working the cart enables Nedved to describe each ingredient to the customer as he adds it to the tacos.

“When they’re eating the food they’re really taking a minute, ‘Now I’m tasting everything he described. I can pick out every single flavor, and I can see how that helps or what I like about it,’” Nedved said. “You can pick out the smokiness of the meat … The sweet chili, you’ll be able to pick that out, see how that ties in with the cilantro sour cream, the pico, and then if you throw in the hot sauce, it adds a different twist into there.”

Nedved imagined that, with the cart, many of the cars going by must think he’s nuts on the side of the corner. However, as soon as one or two people got in line, more would follow.

“There’s a saying in the restaurant/bar industry that nothing attracts a line like a line,” Nedved said. “In other words, everyone wants to do what everyone else is doing.”

Being in a cart, however, left the business exposed in other ways.

“No one wants to stand outside and wait in line if it’s raining,” Nedved said. “If it’s 99 degrees and you’re sitting behind a grill right there, it feels like you’re in a 130 degrees in that one little square spot.”

Wind was another condition that played a part when working the cart.

“I learned if the wind there was anything over 13 mph, which isn’t even that windy, it would lift a tortilla shell off the grill and chuck it into the middle of the street,” Nedved said.

This meant that for some days, it wasn’t worth operating.

“It would blow the burners out or throw tortilla shells or the lettuce would fly out. It would be a wild time trying to figure it out,” he said. “It made for funny conversations, people were very understanding.”

Being in those exposed conditions made the business appear vulnerable, which customers sometimes viewed with sympathy – or with skepticism.

“Some people just want to assume their food is made inside of a hospital where everything has been bleached,” Nedved said. “There’s other people who are going to drive by and be like, ‘I don’t even care what he’s making, I want to go eat what he has.’”

Nedved believes his efforts with the cart demonstrated his love for the business.

“Clearly I wasn’t sitting on the corner because that’s where the millions were,” he said. “I just enjoyed what I was doing, and I was having fun.”

Following the success of his tacos, Nedved decided to change the name of his business.

“As [the truck and cart] were going, it was very clear that the people wanted the taco guy. No one even remembered what my old food truck was except for the guys that were on that jobsite,” Nedved said.

“Everybody wanted the taco guy, they were trying to book the taco guy to different events and things like that, so eventually, at the end of the year, we bought another trailer. We converted it to [The Papillion Taco Guy] and took the other trailer and sold it,” he explained.

After running both the trailer and cart, the business was able to take a leap into a bigger market by leasing their own restaurant.

“We put ourselves in a position where we didn’t have to force ourselves here. We could afford to wait for the right opportunity,” Nedved said.

Even with the challenges, having something he built himself makes it all worth it to Nedved.

“In this world you’re either going to spend your time building somebody else’s dream or building your own. I just wanted to chase my own,” Nedved said, “and even if I failed, I just wanted to know if I could do it.”

To continue outreach to the community, Nedved said his business was researching what it takes to become a foundation and give away scholarships.

“We’re probably not paying for anyone’s first semester of college,” he said. “If anything, we might just give away some small scholarships, but I can say, ‘Listen, I’m only giving scholarships away to the schools in my community,’” Nedved said. “Not 12 kids out of the entire state of Nebraska or the entire nation.”

“It would be cool if every company in the world helped to a significant amount to do something in their communities that they affect,” Nedved said.