Sludge consumption clogs brains

You swipe up. At the top of your screen is a classic scene from “Family Guy,” and at the bottom, Jake from Subway Surfers. You swipe up. At the top left of your screen is an interview with Harry Styles at 1.5x speed, at the top right is a knife gliding through kinetic sand, and at the bottom, a disembodied hand plunging into a tub of slime. You swipe up.

TikTok has achieved a new standard of engagement. Overstimulating collages, like those described above, have pervaded the platform in recent months, outperforming even the most popular standalone videos. Unrelated clips in triptych compositions might not be nutritious, but they’re frighteningly easy to consume; it’s nearly impossible to look away.

These internet salads are affectionately referred to as “sludge content.” They’ve proliferated on TikTok, where copyright restrictions are almost nonexistent, and clips from shows such as “Family Guy” are used apparently without penalty. TikTok is the most fitting milieu; “duets,” splitscreen collaborations, have long been a staple of the platform, and the sheer variety of its content in general predisposes TikTok to sludge’s overwhelming recombinations.

Sludge plays on the internet’s preexisting themes, while taking advantage of new trends. The individual videos constituting sludge have historically appealed to users: ASMR, mobile gameplay, and bootlegged television clips are internet traditions, tried and true. Why not combine them?

The Origin Of Niches

People use the internet for a variety of purposes. Whether to participate in a community, broadcast their viewpoints, keep up to date on the news, or view music videos, there is a spot for everyone. These spots are called “niches,” taken from the evolutionary concept in biology. Species must specialize to adapt to what nature demands, while the internet must specialize to adapt to what users want. If a website or channel is removed or taken down, another is free to fill their niche and adopt previous users.

Rejecting this naturalistic and user-driven ideal, sludge fills no niche. Nobody asked for it, and never before has there been anything like it.

TikTok scrollers, notably young people, are often faulted for an incapacity to focus, and many erroneously blame such users for the invention and influence of sludge content. While this age group does tend to consume more sludge, it did not create the form. Nor did the form materialize in response to a need, a want, or a gap in the internet’s evolutionary tree. So where did sludge come from?

TikTok, among other social media, works like a game. It functions according to an algorithm, an algorithm that rewards the completion of certain tasks. The most desirable thing to the algorithm is “viewer retention,” or having viewers watch to the end of a video and stay on the app. Posts with a greater viewer retention are promoted over less attention-holding content. The most retentive videos become the most popular videos, and if you made them, you win. Typically, the prize is cash, TikTok’s recompense for the advertisements served alongside your video.

No content formula has proved more potent for retaining viewers than sludge. Syllogistically, this makes sludge the natural option for a person, or a group of people, trying to make a quick buck online. It is low effort, high reward. With basic video editing software, a person can produce several dozen visual hodgepodges a day, and a team of people working within a content farm can produce hundreds. The average sludge fan can watch even more.

Surrendering to the Algorithm

Most people are able to tell that something isn’t quite right with sludge content. Even for users who get the vibe that their attention is being abused, it is infinitely easier to enjoy it than to question it. As one user commented on a sludge video, “my mind feels whole.”

Millions of people spend hours a day vaguely enjoying sludge. Hypnotized by indulgent medleys of movement and sound, it’s hard to think of anything else. It’s a dissociative, almost dehumanizing experience.

“TikTok doesn’t reward videos made for human beings. It rewards videos made for human attention spans,” says commentator Lily Alexandre in her YouTube video essay entitled “Everything Is Sludge: Art in the Post-Human Era.” In the video, she explains that the most popular TikToks are usually not the ones people would prefer to see, nor the ones that would be most beneficial.

Instead, videos that appeal to ancient gratification instincts, as well as to the modern short attention span, outperform the rest. Sure, you might find greater personal fulfillment in consuming thoughtful films, art, or music, but it’s a lot quicker and easier to devour what the algorithm feeds you.

Alexandre points out that a TikTok user must surrender control in order to use the platform. On most video services, such as Netflix and HBO Max, you have to explicitly choose what you’ll watch. You don’t have that liberty on TikTok. You’re able to influence the algorithm with “Likes” and “Not Interested’s,” but the machine decides what you’ll see. TikTok is popular largely because it removes one of pleasure’s greatest inconveniences: choice. It’s almost soothing to be swaddled helplessly in the arms of the algorithm.

IPad Kids

YouTube has a feature, called autoplay, that similarly removes human decision from the equation. This feature frequently is used by parents, so that their children can be continuously occupied by a stream of presumably age-appropriate content. Designed specifically for these younger audiences, YouTube Kids provides ample employment for idle infants.

Mysteriously, specialized media platforms and uninvolved parenting have produced a population of toddlers addicted to the internet. Beholden to the whims of sidebar recommendations, some children spend hours a day watching Cocomelon animations and Finger Family singalongs. They are a passive audience; they don’t know any better than to watch what’s put in front of them.

In response to the “iPad kid” phenomenon, YouTube has been flooded with mediocre rehashings of tropes characteristic to children’s media. Studios of untraceable origin steadily churn out content tailored to toddlers, featuring bright colors, unoffending music, familiar characters, simple plots, and toy unboxings.

Such videos rack up millions of views, primarily from children left unattended on personal devices. Because children will watch anything that holds their attention, they’re the perfect audience to exploit for ad revenue. Hence, cheap production studios liberally invest in sites like YouTube Kids.

With no standard for quality, many videos marketed toward children are nonsensical. Historically, some have contained disturbing, violent, or otherwise inappropriate themes. Children impartially consumed videos containing extremely hostile elements, and the issue went majorly unresolved until YouTube announced a thorough cleanse of their Kids platform in late 2017.

Alexandre claims that the scandal of unsuitable and exploitative kids content on YouTube is analogous to the sludge situation; only in this case, it is not naive children who are being victimized, but usually full-grown adults. Mesmerized by familiar and engrossing content, we’re reduced to a childlike passivity.

Don’t Be A Baby

If you’re reading this, you’re probably not a baby. As adolescents and adults, you and I have the knowledge and the capacity to make choices about the media we consume. Though many take the role of the toddler watching on autoplay, we all can be the parent who turns it off.

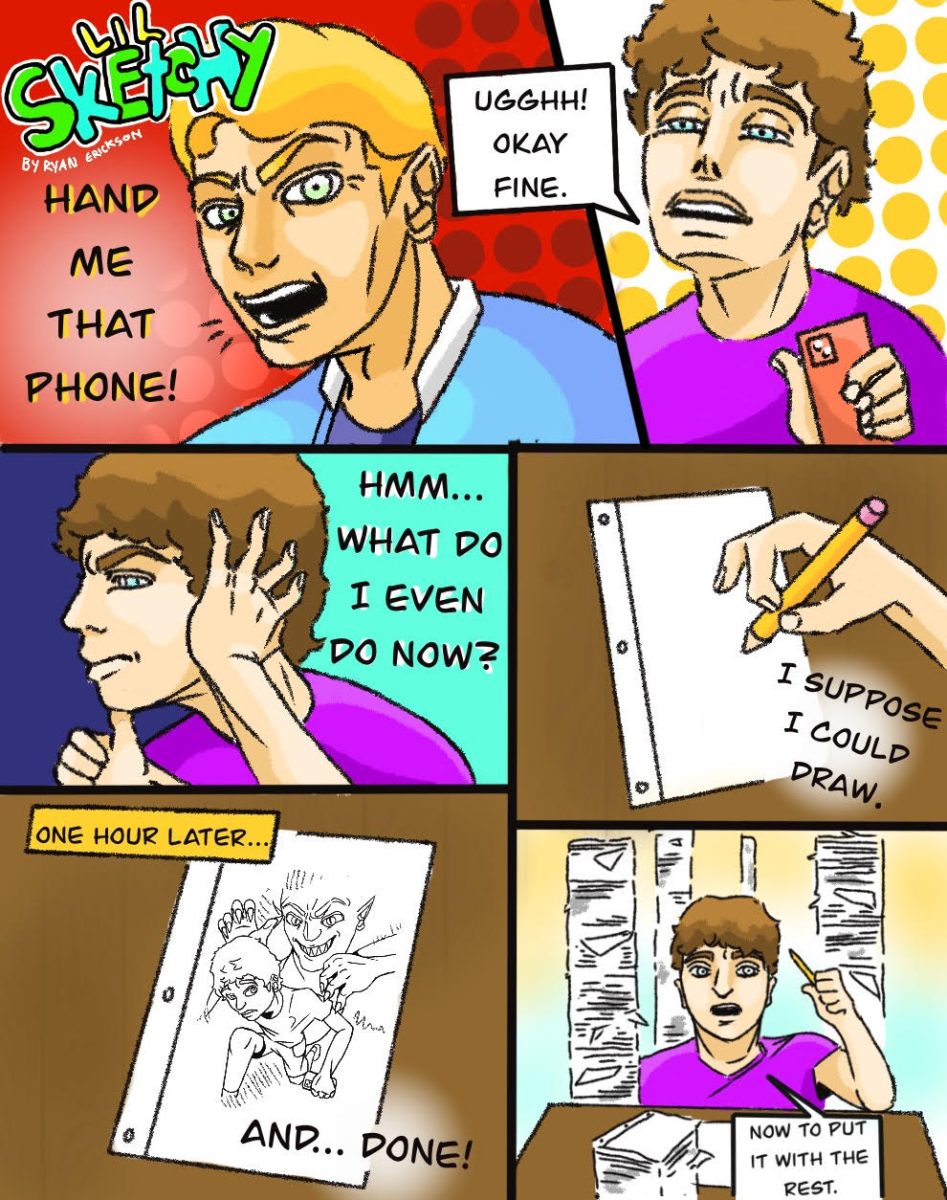

If I don’t know what to do, it’s always been my habit to grab my phone and open YouTube, TikTok, or the news. When I put the phone away, though, the boredom is still there. Scrolling and staring didn’t fix anything. I don’t know what to do, so I pull the phone back out.

Sludge is a never-ending pursuit; there is no goal, no denouement, and no satisfaction. You’ll keep coming back to it, and you’ll be in the same place when you put it away. In some ways, it’s like a drug. Addictive and escapist, sludge can prove ruinous to our attention span and productivity. Though immediately gratifying, it offers nothing in the long run.

The algorithms, the content farms, and the copyright laws are not going to change. It lies in our hands to be intentional with how we feed our minds and spend our time. We live at a time when everything is available to us, clamoring for our focus. Unless we figure out what really matters to us, and actively decide to seek those things out, our attention will continue to be abused for ad revenue by kinetic sand and Peter Griffin.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Papillion-La Vista South High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

![Pictured above is a structure that displays the names of Nebraska Vietnam veterans in order to “honor [their] courage, sacrifice and devotion to duty and country.”](https://plsouthsidescroll.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Trey_092625_0014-e1760030641144-1200x490.jpg)